Recompilation hell: what it feels like

Elixir is an amazing language and it’s been a huge privilege being able to work with it for over a decade now (how time flies)!

I’d like to point out an issue that, if overlooked, can severely impact productivity in your team. Yes, I’m talking about module (re)compilation.

You make a few changes to a single file in your codebase and hit recompile. Boom: Compiling 93 files (.ex). Then you make another change and boom: Compiling 103 files (.ex).

We’ve all been there. There is a solution to this problem. Whether the solution is painful depends on how long this problem has gone unaddressed in your codebase.

If you don’t actively fix this, the number of recompiled files will likely grow as your project grows, and the harder it will be to get rid of it.

Why it matters

Before sharing how to detect, fix and prevent it from ever happening again, I’d like to briefly go over why it matters and why you should absolutely care about this.

The feedback time, that is, the time it takes for a developer to iterate between making changes and observing the changes is the single, most important individual productivity metric you should monitor.

Tighten your feedback loop: if you change one module, ideally only one module should recompile. If you are doing localhost web development, your localhost page should have near-instant page loads. There are exceptions to this, but if you are the exception you are conscious that you are the exception.

Step 1: Detecting the issue

Well, detecting is easy: you change one module and several ones get recompiled? Yep, you are in recompilation hell. But how can you know in which circle of hell are you in?

You can use the most underestimated tool in the Elixir ecosystem!

A primer on mix xref

mix xref is, without a doubt, the most underestimated tool[0] in the Elixir ecosystem. Think of it as being a swiss army knife that provides insights in the relationships between modules in your codebase.

It can help you:

List all compile-time dependencies in a project

mix xref graph --label compileList all files that depend on foo.ex at compile time

mix xref graph --label compile --sink lib/foo.ex --only-nodesList all callers of a given module

mix xref callers Core.Schemas.AdminList every dependency that is linked to a particular file

mix xref trace lib/foo.exGenerate a graph with all compile-time dependencies

mix xref graph --format dot --label compiledot -Tsvg xref_graph.dot -o xref_graph.svg

Step 2: Understanding the issue

Okay, you know you are in recompilation hell. But do you know why you are in hell? My guess is: you’ve sinned with macros.

In order to fully comprehend the issue, you will need first to understand the interaction between modules and what creates a compilation dependency.

Module (re)compilation in Elixir

Let’s understand, once and for all, how modules recompile in Elixir.

Scenario 1: runtime dependencies

In this first scenario, there are only runtime function calls: A1 calls B1 which calls C1.

|

|

Here’s the output of mix xref graph: [1]

|

|

It tells us that lib/a1.ex has a runtime dependency to lib/b1.ex, which in turn has a runtime dependency to lib/c1.ex, which has no dependencies.

NOTE: We can tell this is a runtime dependency because the

mix xrefoutput has no additional information next to the file path. If they were compile-time dependencies, we’d see “lib/a1.ex (compile)” instead.

Recompilation output when changing any of these modules individually:

| lib/a1.ex | lib/b1.ex | lib/c1.ex |

|---|---|---|

| Compiling 1 file | Compiling 1 file | Compiling 1 file |

Runtime dependencies are great because it means that changing one module will require recompilation of only that one module. In an ideal world, every module in your codebase would only depend on other modules at runtime.

Scenario 2: compile-time dependencies

Alas, we don’t live in an ideal world. Let’s simulate a compile-time dependency

|

|

As you probably know, module attributes are evaluated at compile-time (this is actually why you should use Application.compile_env/3 in module attributes). What that means for the code above is that:

- The

@battr inA2holds an:Elixir.B2atom that references theB2module - The

@personattr inB2holds the:mikeatom, which came from the call toC2.get_person/0

Elixir quiz time: which modules above will have a compilation-time dependency?

Click to see output of mix xref graph

lib/a2.ex

└── lib/b2.ex

lib/b2.ex

└── lib/c2.ex (compile)

lib/c2.ex

As one would expected, B2 depends on C2 during compile-time, since if we modify the result of C2.person/0 to be,

ahem, :joe, B2 will need to be re-compiled so that the @person module attribute can be re-evaluated.

Somewhat surprisingly, A2 does not have a compile-time dependency on B2. The compiler is smart enough to track that any changes in the B2 module would never cause the @b value to change.

Recompilation output when changing any of these modules individually:

| lib/a2.ex | lib/b2.ex | lib/c2.ex |

|---|---|---|

| Compiling 1 file | Compiling 1 file | Compiling 2 files |

Should we worry about these compile-time dependencies? Personally, I wouldn’t worry too much until they become a noticeable issue. They may become noticeable when you start, for example, calling a particular function from a module attribute across several modules.

The reason I wouldn’t bother initially is that this kind of compile-time dependency is usually easy to resolve. So go ahead, let your codebase evolve and grow, and if you get any sharp edges you can fix them later on.

Of course, that doesn’t mean you can be negligent about this. When writing or reviewing code, always pay extra attention to module attributes. If you see a compilation dependency that has the potential to become nasty in the future — or that can be easily removed right away — go ahead and save yourself from future headaches.

Scenario 3: transitive compile-time dependencies

The third scenario I’d like to showcase is when your code has transitive compile-time dependencies. If you are suffering from recompilation pain, you are likely hitting this scenario.

Below is the smallest demo I could think of:

|

|

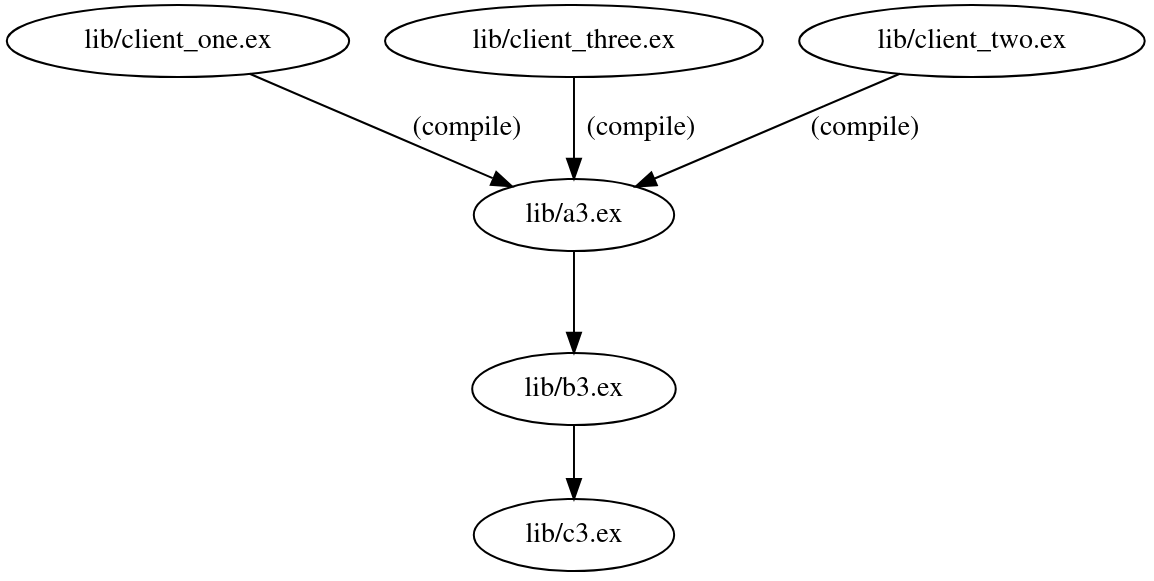

You have three “clients”. Clients are simply users of A3 (with a regular compile-time dependency). A3 then has a runtime dependency on B3, which also has a runtime dependency on C3. That doesn’t sound too bad, right? Most importantly, it seems to be a regular occurrence in any given codebase.

Here, what I meant by “client” is that there may be several instances using

A3. Think events or endpoints or jobs, each of which with a compile-time dependency to their “core” implementation.

This is what the compilation graph for these modules looks like:

Looking at the graph above, we expect that changes to lib/a3.ex will cause all N clients of it to be recompiled. Indeed, that’s exactly what happens. But what would you expect to be recompiled if you were to change lib/c3.ex?

Only C3, right? Yes, me too. But here’s what happens when I change C3:

|

|

Ouch, not good. What we are witnessing here is transitive compile-time dependencies in action.

| lib/client_one.ex | lib/a3.ex | lib/b3.ex | lib/c3.ex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compiling 1 file | Compiling 4 files | Compiling 4 files | Compiling 4 files |

While my minimal example seems out of touch from reality, usually you will hit this scenario when:

- You have a

Core.Eventimplementation with a macro - You have multiple

Event.MyEventNamemodules that use macros fromCore.Event - You call

Services.Logfrom within the macro - You call

Services.Userfrom withinServices.Log - You call

Schemas.Userfrom withinServices.User

Every time you change your user schema, you are also recompiling every single one of your events.

Now imagine you follow a similar pattern with endpoints, job definitions, schemas, authorization, error handling, data validation, analytics. You can easily find yourself in a scenario where everything is tangled in a web of modules. One change basically recompiles every single module in your codebase.

This is the worst! This is the eight circle of hell! It has the potential to bring your productivity down by multiple orders of magnitude! Do yourself (and your team) a favor and get rid of them — or monitor them closely so they don’t grow inadvertently.

In practice, the worst offenders of this are macros. You might be affected even if you don’t write macros yourself: “macro-heavy” libraries, in particular, are prone to transitive dependencies (Absinthe is worth mentioning by name: every codebase I’ve seen using Absinthe suffers from this).

Step 3: Fixing the issue

At this point, you know you are in hell, and more importantly you know why you are in hell. How can you get out, then? It basically boils down to two simple steps:

- Identifying the offending modules in key or common areas of your codebase; and

- Refactoring them to not create compile-time dependencies.

Will this be difficult? It depends on how “spaghettified” your modules are. If you have a big ball of mud, untangling your dependencies is likely to be painful.

No matter how difficult this task turns out to be, however, I can guarantee you it’s definitely worth the effort. And once untangled, if you keep reading this blog post until the end, you will learn what you have to do to prevent transitive dependencies from ever happening again.

Identifying transitive dependencies

Let’s go! First, you will need to identify what are the affected modules.

The easiest thing you can do is:

- Modify a module that triggers several other modules to recompile.

- Run

mix compile --verbose.

Now you have a list of every module that was recompiled.

But we can do better than that! We can get the full “path” between two files using mix xref. This will make it substantially easier for you to understand exactly where the tangling is happening:

mix xref graph --source SOURCE --sink TARGET

Here,

TARGETis the file you changed and triggered recompilation of several unrelated files, andSOURCEis the module you think (or know) is starting the compilation chain. If you don’t know which module is theSOURCE, simply use the last file shown in themix compile --verbosecommand you ran above. It is likely theSOURCEyou want.

Below is the output for Scenario 3 discussed previously:

|

|

In the example above, if you can either remove the compilation dependency between client_one.ex and a3.ex or remove the runtime dependency between a3 and b3, you will break the compilation chain.

Getting rid of compile-time dependencies

You have identified the compilation chain and now you need to break it. Below you will find a few strategies that you can use to refactor the offending modules.

Strategy 1: Move macros to dedicated modules with no additional dependencies

Initially, we have a Core.Event module that has both the macros and the generic functions that may be used by events.

|

|

Notice how Services.Log ends up as part of the compilation chain simply because it is part of the Core.Event module, even though it plays no special role in the macro itself. The command below tells us that there exists a transitive dependency (mix ref refers to them as “compile-connected”) between event_user_created.ex and core_event.ex

|

|

This strategy consists in breaking Core.Event into two parts: Core.Event.Definition with the macros and Core.Event with shared functions.

|

|

One thing to keep in mind here is that your Definition module should not have compile-time dependencies to other parts of your application, otherwise you are back to square one.

If you can’t get around calling another module within your codebase, try to follow the same pattern: make sure to extract the necessary functions into a dedicated module. The goal is to isolate the functions needed by the macro into their own modules.

By applying this strategy, we are now free of transitive dependencies:

|

|

You can find the full example in Github.

Strategy 2: Reference the module during runtime (Absinthe example)

This strategy (ahem hack) consists in referencing the module during runtime execution, in order to break the chain between queries.ex and resolver.ex.

|

|

Here’s the alternative:

|

|

But Renato, is it safe? Can’t this cause some module being stale due to it not recompiling? This is a good question. And I don’t have a good answer, except that I’ve been using this hack strategy for at least 8 years and don’t remember a single instance where it caused inconsistencies.

The downsides of this approach are:

- Worse code readability, since you are doing something unexpected.

- Worse performance, since you are requiring additional function calls.

Are the downsides worth the advantage of not having a compilation chain? Almost always, yes! The degraded readability can be abstracted away (as can be seen in the example). The performance overhead is negligible in most cases (a single SQL query will be at least 10,000x slower).

This strategy is particularly useful for Absinthe: when you break the chain between your queries/mutations and resolvers, you are effectively shielding yourself from transitive dependencies that could potentially impact your entire codebase!

You can find the full example in Github.

Strategy 3: Keep macros simple

My third strategy is that, whenever possible, keep your macros simple. In other words, make sure they only reference built-in modules and/or 3rd-party libraries.

If your macro absolutely needs to call some of your own code, then try to isolate that particular code into a single, dedicated module with no external dependencies (this is Strategy 1, actually).

Strategy 4: Don’t use macros

Macros are tempting, I know. Can you not use them at all? If that’s a valid option, I recommend you take it.

Macros have the downsides of making code harder to read, harder to test, harder to document, less intuitive and less idiomatic. On the other hand, they have the positives of reducing boilerplate and ensuring consistency and conventions across a codebase.

If you actually need them, make sure you keep them simple (Strategy 3).

Step 4: Preventing it from ever happening again

After a lot of work, you managed to get rid of compilation chains! Congratulations! Your co-workers will be very grateful for your refactor.

Detecting transitive dependencies in your CI pipeline

First, you need to know how many chains you currently have:

|

|

Above command will tell you the number of compile-connected (transitive) dependencies you have.

Then, you can apply the following verification in your pipeline:

|

|

Replace NUMBER with your current (or target) number of transitive dependencies in your codebase. Your goal should be zero.

Following this method, you will prevent:

- new chains from showing up.

- existing chains from growing up.

Wait! You do have a CI pipeline, right? If you don’t have one but you are using Github, just add this basic workflow template. It compiles, tests, checks formatting and transitive dependencies. That’s a good starting point. Github Actions is free, including private repositories.

Worth mentioning

Pattern-matching on structs no longer creates compile-time dependencies

If you’ve been working with Elixir for several years, you might remember this used to be a problem in the past:

|

|

Above code would create a compile-time dependency between Services.User and Schemas.User. Since Elixir 1.11 (~2020) this is no longer the case. Now, this kind of pattern-match creates an “export” dependency, which will only trigger a recompilation if the struct of Schemas.User changes.

Takeaway: don’t be afraid of aliasing and pattern-matching against a struct. It makes your code better, safer, easier to read and won’t cause unnecessary compile-time dependencies.

Don’t (blindly) rely on mix xref for boundaries

As you saw in Strategy 2, a module can reference another dynamically. When that happens mix xref is not able to tell you that A may be calling B.

Takeaway: don’t blindly trust the

mix xrefoutput, especially if you are trying to enforce security/boundaries across modules.

Visualizing your dependencies with DepViz and Graphviz

There’s this amazing tool that you should use right now: DepViz.

- Simply go to https://depviz.jasonaxelson.com/.

- Generate your

.dotfile withmix xref graph --format dot. - Upload and visualize your clean, well-organized module structure.

Alternatively, you can simply use Graphviz:

- Generate your

.dotfile withmix xref graph --format dot. - Generate a

.svgof your graph withdot -Tsvg xref_graph.dot -o xref_graph.svg. - Open it in your browser (or whatever) and visualize your module hierarchy.

Conclusion

Whether you are a CTO, a tech lead or an individual contributor in a team, please, for your own sake, pay attention to your feedback loop.

When starting a new project, an experienced engineer will keep a close eye on this, for they know how important it is in the long term to have a fast loop. However, less experienced engineers, or experienced engineers who don’t have a lot of experience with Elixir might not realize they are hurting the feedback loop until it gets too late.

Optimize the feedback loop your developers (or you) go through on a daily basis. I insist: when it comes to productivity, this is the first metric you should care about.

This blog post should contain everything you need to identify and permanently fix (re)compilation issues with your codebase. However, if you have questions or comments, feel free to reach out to me via email.

Notes

[0] - If you disagree with this assertion, please shoot me an email. I’d love to hear what you consider to be more underestimated than mix xref. ^

[1] - This originally read mix xref --graph; however, the correct command is mix xref graph. Thanks to Sam Weaver (and team) for pointing out this issue! ^